Safe Retries

Protect your database from the 'double-tap' by implementing idempotency keys that make retrying requests boringly safe.

Imagine a network timeout occurs at the exact millisecond after your database commits a transaction but before the response packet leaves the server rack. The client sees a 504 Gateway Timeout. They do what any reasonable person (or automated retry policy) does: they hit the endpoint again. If that endpoint is /v1/charges, your customer just paid twice for one pair of shoes. This is the "double-tap" problem, and it's the fastest way to lose a user's trust.

Networking is messy. Distributed systems are messier. You cannot guarantee a request will only arrive once, but you can guarantee that processing it twice has no additional effect. This is the essence of idempotency.

The Idempotency Key

The industry standard for solving this is the Idempotency-Key HTTP header. The client generates a unique string—usually a UUID—and sends it with the request. On the server side, we use this key to identify if we've seen this specific _intent_ before.

It’s not enough to just check if a record exists. You need a dedicated mechanism to track these keys. Here is how a typical flow looks in a Node.js/PostgreSQL environment:

async function processPayment(

userId: string,

amount: number,

idempotencyKey: string

) {

return await db.transaction(async (tx) => {

// 1. Check if we've already handled this key

const existing = await tx.idempotencyKeys.findUnique({

where: { key: idempotencyKey },

})

if (existing) {

// If we found it, return the cached response immediately

return JSON.parse(existing.responseBody)

}

// 2. Perform the actual business logic

const charge = await stripe.charges.create({ amount, customer: userId })

// 3. Store the result along with the key

const response = { status: 'success', chargeId: charge.id }

await tx.idempotencyKeys.create({

data: {

key: idempotencyKey,

responseBody: JSON.stringify(response),

userId: userId,

},

})

return response

})

}The "Locking" Problem

The code above has a subtle, dangerous flaw: race conditions. If a client sends two identical requests 10ms apart, both might pass the findUnique check before the first one has finished the create call. You’ll end up running the logic twice anyway.

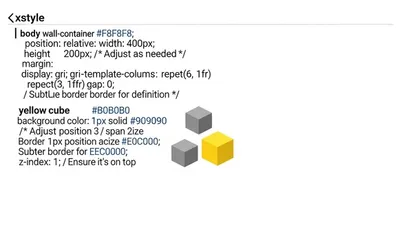

To fix this, you need an atomic "claim." You can use a database constraint or a distributed lock (like Redis). I prefer using a state column in the idempotency table: STARTED, COMPLETED, or FAILED.

When a request comes in, try to insert a record with status: STARTED. If the insert fails because the key already exists, you know a request is either currently in flight or already done.

What about failures?

Not all retries are created equal. If the database crashes mid-process, you want the next retry to actually try again. If the request failed because of a validation error (400 Bad Request), you might want to cache that error so you don't waste CPU cycles re-validating the same garbage input.

I usually follow these rules:

- Cache 2xx and 4xx results. These are "deterministic" outcomes.

- Do not cache 5xx results. A 500 often means a transient issue (like a database being down). We _want_ the retry to actually execute the logic again once the system recovers.

- Set an expiration. Idempotency keys shouldn't live forever. 24 to 48 hours is usually the sweet spot for handling retry loops without bloating your database into oblivion.

The Client's Responsibility

A common mistake I see is developers generating the idempotency key on the _server_ and sending it back to the client for future use. This is backwards.

The client must own the key. The client knows their intent. If the client’s mobile app crashes before it even sends the request, it should persist that key to local storage so that when the app reboots, it can send the _exact same_ key for that specific purchase attempt.

Making it Boring

Implementation usually feels like overkill until the day a load balancer flicker triggers a wave of 409 Conflict errors instead of a wave of duplicate entries. That's when you realize that idempotency transforms a high-stakes "will it or won't it" disaster into a boring, predictable log entry.

In software engineering, boring is a feature. Write your code so that even when the network is screaming, your database stays calm.